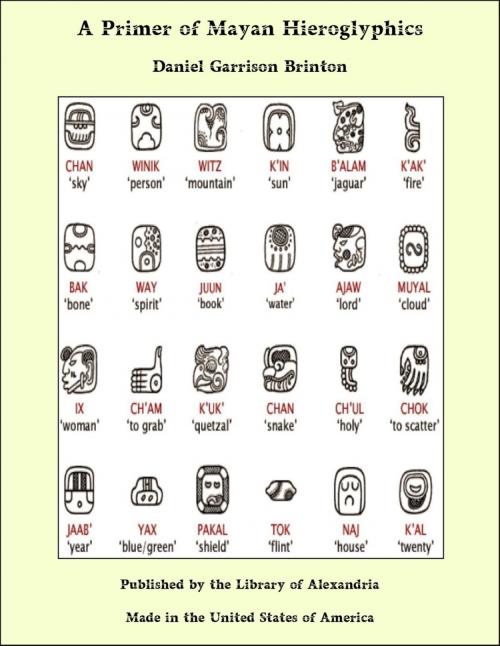

A Primer of Mayan Hieroglyphics

Nonfiction, Religion & Spirituality, New Age, History, Fiction & Literature| Author: | Daniel Garrison Brinton | ISBN: | 9781465622082 |

| Publisher: | Library of Alexandria | Publication: | March 8, 2015 |

| Imprint: | Language: | English |

| Author: | Daniel Garrison Brinton |

| ISBN: | 9781465622082 |

| Publisher: | Library of Alexandria |

| Publication: | March 8, 2015 |

| Imprint: | |

| Language: | English |

One and the same hieroglyphic system is found on remains from Yucatan, Tabasco, Chiapas, Guatemala, and Western Honduras; in other words, in all Central American regions occupied at the Conquest by tribes of the Mayan linguistic stock. It has not been shown to prevail among the Huastecan branch of that stock, which occupied the valley of the river Panuco, north of Vera Cruz; and, on the other hand, it has not been discovered among the remains of any tribe not of Mayan affinities. The Mexican manuscripts offer, indeed, a valuable ancillary study. They present analogies and reveal the early form of many conventionalized figures; but to take them as interpreters of Mayan graphography, as many have done, is a fatal error of method. In general character and appearance the Mayan is markedly different from the Mexican writing, presenting a much more developed style and method. Although the graphic elements preserved in the manuscripts and on the monuments vary considerably among themselves, these divergencies are not so great but that a primitive identity of elements is demonstrable in them all. The characters engraved on stone or wood, or painted on paper or pottery, differ only as we might expect from the variation in the material or the period, and in the skill or fancy of the artist. The simple elements of the writing are not exceedingly numerous. There seems an endless variety in the glyphs or characters; but this is because they are composite in formation, made up of a number of radicals, variously arranged; as with the twenty-six letters of our alphabet we form thousands of words of diverse significations. If we positively knew the meaning or meanings (for, like words, they often have several different meanings) of a hundred or so of these simple elements, none of the inscriptions could conceal any longer from us the general tenor of its contents. It will readily be understood that the composite characters may be indefinitely numerous. Mr. Holden found that in all the monuments portrayed in Stephen’s Travels in Central America there are about fifteen hundred; and Mr. Maudslay has informed me that according to his estimate there are in the Dresden Codex about seven hundred. Each separate group of characters is called a “glyph,” or, by the French writers, a “katun,” the latter a Maya word applied to objects arranged in rows, as soldiers, letters, years, cycles, etc. As the glyphs often have rounded outlines, like the cross-section of a pebble, the Mayan script has been sometimes called “calculiform writing” (Latin, calculus, a pebble).

One and the same hieroglyphic system is found on remains from Yucatan, Tabasco, Chiapas, Guatemala, and Western Honduras; in other words, in all Central American regions occupied at the Conquest by tribes of the Mayan linguistic stock. It has not been shown to prevail among the Huastecan branch of that stock, which occupied the valley of the river Panuco, north of Vera Cruz; and, on the other hand, it has not been discovered among the remains of any tribe not of Mayan affinities. The Mexican manuscripts offer, indeed, a valuable ancillary study. They present analogies and reveal the early form of many conventionalized figures; but to take them as interpreters of Mayan graphography, as many have done, is a fatal error of method. In general character and appearance the Mayan is markedly different from the Mexican writing, presenting a much more developed style and method. Although the graphic elements preserved in the manuscripts and on the monuments vary considerably among themselves, these divergencies are not so great but that a primitive identity of elements is demonstrable in them all. The characters engraved on stone or wood, or painted on paper or pottery, differ only as we might expect from the variation in the material or the period, and in the skill or fancy of the artist. The simple elements of the writing are not exceedingly numerous. There seems an endless variety in the glyphs or characters; but this is because they are composite in formation, made up of a number of radicals, variously arranged; as with the twenty-six letters of our alphabet we form thousands of words of diverse significations. If we positively knew the meaning or meanings (for, like words, they often have several different meanings) of a hundred or so of these simple elements, none of the inscriptions could conceal any longer from us the general tenor of its contents. It will readily be understood that the composite characters may be indefinitely numerous. Mr. Holden found that in all the monuments portrayed in Stephen’s Travels in Central America there are about fifteen hundred; and Mr. Maudslay has informed me that according to his estimate there are in the Dresden Codex about seven hundred. Each separate group of characters is called a “glyph,” or, by the French writers, a “katun,” the latter a Maya word applied to objects arranged in rows, as soldiers, letters, years, cycles, etc. As the glyphs often have rounded outlines, like the cross-section of a pebble, the Mayan script has been sometimes called “calculiform writing” (Latin, calculus, a pebble).