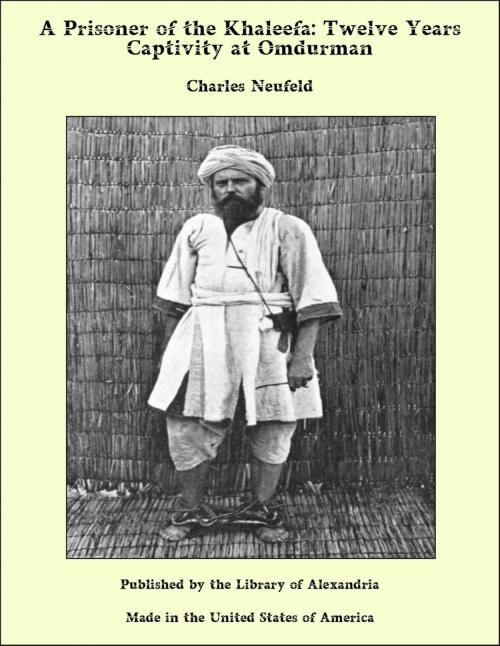

A Prisoner of the Khaleefa: Twelve Years Captivity at Omdurman

Nonfiction, Religion & Spirituality, New Age, History, Fiction & Literature| Author: | Charles Neufeld | ISBN: | 9781465608185 |

| Publisher: | Library of Alexandria | Publication: | March 8, 2015 |

| Imprint: | Language: | English |

| Author: | Charles Neufeld |

| ISBN: | 9781465608185 |

| Publisher: | Library of Alexandria |

| Publication: | March 8, 2015 |

| Imprint: | |

| Language: | English |

Within seventy-two hours of my arrival in Cairo from the Soudan, I commenced to dictate my experiences for the present volume, and had dictated them from the time I left Egypt, in 1887, until I had reached the incidents connected with my arrival at Omdurman as the Khaleefa’s captive, when I became the recipient of a veritable sheaf of press-cuttings, extracts, letters, private and official, new and old, which collection was still further added to on the arrival of my wife in Egypt, on October 13. My first feelings after reading the bulk of these, and when the sensation of walking about free and unshackled had worn off a little, was that I had but escaped the savage barbarism of the Soudan to become the victim of the refined cruelty of civilization. Fortunately, maybe, my rapid change from chains and starvation to freedom and the luxuries I might allow myself to indulge in, brought about its inevitable result—a reaction, and then collapse. While ill in bed I could, when the delirium of fever had left 2me, and I was no longer struggling for breath and standing room in that Black Hole of Omdurman, the Saier, find it in my heart to forgive my critics, and say, “I might have said the same of them, had they been in my place and I in theirs.” But the inaccuracies written and published in respect to my nationality, biography, and, above all, the astounding inaccuracies published in connection with my capture and the circumstances attending it, necessitate my offering a few words to my readers by way of introduction; but I shall be as brief and concise as possible. I have, both directly and indirectly, been blamed for, or accused of, the loss of arms, ammunition, and monies sent by the Government to the loyal Sheikh of the Kabbabish, Saleh Bey Wad Salem. Some have gone so far as to accuse me of betraying the party I accompanied into the hands of the dervishes; a betrayal which led eventually to the virtual extermination of the tribe and the death of its brave chief. The betrayal of the caravan I accompanied did lead to this result; it also led me into chains and slavery. According to one account, I arrived at Omdurman on the 1st or 7th of March (both dates are given in the same book), 1887; yet, at this time, to the best of my recollection, the General commanding the Army of Occupation in Egypt, General Stephenson, was trying in Cairo to persuade me to abandon my projected journey into Kordofan. In a very recent publication, in the preface to which the authors ask their readers to point out any inaccuracies, I am credited with arriving as a captive at Omdurman in 31885, when at this time I was attached as interpreter to the Gordon Relief Expedition, and stood within a few yards of General Earle at the battle of Kirbekan when he was killed. It is probable I was the last man he ever spoke to.

Within seventy-two hours of my arrival in Cairo from the Soudan, I commenced to dictate my experiences for the present volume, and had dictated them from the time I left Egypt, in 1887, until I had reached the incidents connected with my arrival at Omdurman as the Khaleefa’s captive, when I became the recipient of a veritable sheaf of press-cuttings, extracts, letters, private and official, new and old, which collection was still further added to on the arrival of my wife in Egypt, on October 13. My first feelings after reading the bulk of these, and when the sensation of walking about free and unshackled had worn off a little, was that I had but escaped the savage barbarism of the Soudan to become the victim of the refined cruelty of civilization. Fortunately, maybe, my rapid change from chains and starvation to freedom and the luxuries I might allow myself to indulge in, brought about its inevitable result—a reaction, and then collapse. While ill in bed I could, when the delirium of fever had left 2me, and I was no longer struggling for breath and standing room in that Black Hole of Omdurman, the Saier, find it in my heart to forgive my critics, and say, “I might have said the same of them, had they been in my place and I in theirs.” But the inaccuracies written and published in respect to my nationality, biography, and, above all, the astounding inaccuracies published in connection with my capture and the circumstances attending it, necessitate my offering a few words to my readers by way of introduction; but I shall be as brief and concise as possible. I have, both directly and indirectly, been blamed for, or accused of, the loss of arms, ammunition, and monies sent by the Government to the loyal Sheikh of the Kabbabish, Saleh Bey Wad Salem. Some have gone so far as to accuse me of betraying the party I accompanied into the hands of the dervishes; a betrayal which led eventually to the virtual extermination of the tribe and the death of its brave chief. The betrayal of the caravan I accompanied did lead to this result; it also led me into chains and slavery. According to one account, I arrived at Omdurman on the 1st or 7th of March (both dates are given in the same book), 1887; yet, at this time, to the best of my recollection, the General commanding the Army of Occupation in Egypt, General Stephenson, was trying in Cairo to persuade me to abandon my projected journey into Kordofan. In a very recent publication, in the preface to which the authors ask their readers to point out any inaccuracies, I am credited with arriving as a captive at Omdurman in 31885, when at this time I was attached as interpreter to the Gordon Relief Expedition, and stood within a few yards of General Earle at the battle of Kirbekan when he was killed. It is probable I was the last man he ever spoke to.