| Author: | John V. Dunlap | ISBN: | 9781891053993 |

| Publisher: | Garrett County Press | Publication: | March 20, 2012 |

| Imprint: | Garrett County Press | Language: | English |

| Author: | John V. Dunlap |

| ISBN: | 9781891053993 |

| Publisher: | Garrett County Press |

| Publication: | March 20, 2012 |

| Imprint: | Garrett County Press |

| Language: | English |

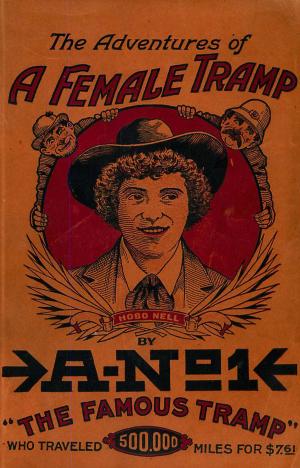

Published in 1922, this seemingly straightforward guide for entrepreneurial women quickly descends into attacks on the reader, unconscious self-hatred and a convoluted sales pitch for a door-to-door pamphlet business. “There must be times in your life when you have flashes of realization,” John V. Dunlap writes (perhaps of himself), “when you must see the fallacy of your ideas. You must realize the wonderful experience and pleasure which you are missing. You are going through life blindly.” This existential angst comes after a variety of short chapters on money-making schemes (a tea shop, a lamp shade business, doughnuts, dyeing, necktie fabrication, among other crafty, Etsy-like suggestions). A section titled, “Would You Like to Own a Shirt Factory” reads like Richard Brautigan: “Every man has trouble buying a shirt that will fit him. One wise girl knew this and turned it into real profit.” Mr. Dunlap spends the last half of How to Make Money convincing the reader to sell books by his publisher, Social Mentor Publications. “Do you know that salesmen are made, not born?” he writes. “Do you know that the demand for salesmen always has and always will be three times greater than the supply?” How to Make Money is a fascinating work infused with the roaring twenties nuttiness of The Great Gatsby, and yet Mr. Dunlap’s frustrated musings and schemes will undoubtedly be familiar to the contemporary wealth seeker.

Published in 1922, this seemingly straightforward guide for entrepreneurial women quickly descends into attacks on the reader, unconscious self-hatred and a convoluted sales pitch for a door-to-door pamphlet business. “There must be times in your life when you have flashes of realization,” John V. Dunlap writes (perhaps of himself), “when you must see the fallacy of your ideas. You must realize the wonderful experience and pleasure which you are missing. You are going through life blindly.” This existential angst comes after a variety of short chapters on money-making schemes (a tea shop, a lamp shade business, doughnuts, dyeing, necktie fabrication, among other crafty, Etsy-like suggestions). A section titled, “Would You Like to Own a Shirt Factory” reads like Richard Brautigan: “Every man has trouble buying a shirt that will fit him. One wise girl knew this and turned it into real profit.” Mr. Dunlap spends the last half of How to Make Money convincing the reader to sell books by his publisher, Social Mentor Publications. “Do you know that salesmen are made, not born?” he writes. “Do you know that the demand for salesmen always has and always will be three times greater than the supply?” How to Make Money is a fascinating work infused with the roaring twenties nuttiness of The Great Gatsby, and yet Mr. Dunlap’s frustrated musings and schemes will undoubtedly be familiar to the contemporary wealth seeker.