Iliad ad Nihilum: Psychê, Conscience, Wonder

Nonfiction, Religion & Spirituality, Philosophy, Existentialism, Aesthetics| Author: | Michael Degener | ISBN: | 9781310424144 |

| Publisher: | Michael Degener | Publication: | March 21, 2015 |

| Imprint: | Smashwords Edition | Language: | English |

| Author: | Michael Degener |

| ISBN: | 9781310424144 |

| Publisher: | Michael Degener |

| Publication: | March 21, 2015 |

| Imprint: | Smashwords Edition |

| Language: | English |

Achilles, paragon of aristocratic valor, an “idol of idiot worshippers,” as Shakespeare’s Thersites soliloquizes? The Renaissance bard’s Troy story, his much disregarded Troilus and Cressida, has long baffled readers; why would Shakespeare satirize the noble epic tradition, the ‘divine’ Homer? The answer: Shakespeare’s parody of Achilles’ tale pays homage to The Iliad, itself already a parody of the traditional tale its author inherited. Shakespeare engages the author of The Iliad, not in any simple way “Homer” as he has been imagined, in a world historical dialog to recover the underpinnings of the Renaissance soul in the Greek exposure to abyssal psychê.

The sixth century author of The Iliad was anything but the naïve, muse-inspired bard he presents as his narrator, nor does his ‘epic’ extol an aristocratic, albeit vexed, Achilles. This original, singular work of art reworks the famous traditional theme of Achilles' wrath, or mênis. The author deploys a revolutionary ad nihilum poesis directed out from the mythos of tradition to the abyss of psyche disclosed through the counter narrative of Achilles’ pothê, the longing that arises from the absence of the fallen leader of a fighting band.

The remarkable failure of generations of readers across the centuries to penetrate to the true meaning and stakes of the work may be attributed not only to the monumentally extended and compounded complexity of its narrative devices, far more complex ultimately than heretofore recognized, but also the trenchant nostalgia, already pilloried four centuries ago by Shakespeare, for naïve mythical origins exploited and critiqued by the author in his own representation of himself as if the mere mortal exponent of the Muse. And this nostalgia for the naïve poet, albeit retranslated from Schiller’s original idealist conception of poetic genius into updated conceptions of still essentially naïve oral poetics, which still holds Homeric Studies in its thrall, continues to propagate methodologies that bear more resemblances to the study of theological traditions than literary or critical studies.

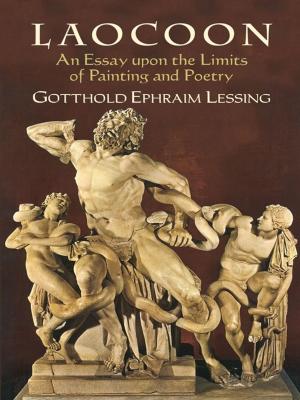

No, not the traditional oral epic. The Iliad, written rather by a single, self-aware, and ironic author in mid-sixth century Athens, unfolds an allegorical critique of the martial aristocracy through Achilles’ relationship with Patroclus. With the onset of his wrath and withdrawal from the fight, Achilles casts his curse of pothê: “someday a longing for Achilles will come upon the sons of Achaeans.” Achilles allows Patroclus, ever at the ready as potential substitute to mitigate the pothê to which his fighting band would be exposed should he fall, rather to substitute for him illegitimately while he still lives. Achilles’ wrath, putative theme of the epic, will, however, only be rescinded once this curse of pothê will have redounded, instead, upon himself with the immitigable pothê he will suffer upon the death of his dearest companion, Patroclus. This pothê occasions Achilles’ exposure to psychê, Patroclus’ psychê, or rather but an imaginary dream vision of such arising as a novel glimmering of conscience. And thus Achilles is exposed to the advent of what is properly human experience, in an unprecedented experience of thauma, or wonder, not so much existential, as ad-sistential; Achilles exposed out there to stand at the limit of the abyss of earth ad nihilum.

The ultimate philosophical dimensions of the study, which offer a crucial step in the recasting of the first movements of the thought of the West, hold out the potential to resuscitate The Iliad, along with Hesiod, for the broader critical audience and thus present another set of demands that generally lie outside the sphere of Homeric or Classical Studies as currently delimited.

Achilles, paragon of aristocratic valor, an “idol of idiot worshippers,” as Shakespeare’s Thersites soliloquizes? The Renaissance bard’s Troy story, his much disregarded Troilus and Cressida, has long baffled readers; why would Shakespeare satirize the noble epic tradition, the ‘divine’ Homer? The answer: Shakespeare’s parody of Achilles’ tale pays homage to The Iliad, itself already a parody of the traditional tale its author inherited. Shakespeare engages the author of The Iliad, not in any simple way “Homer” as he has been imagined, in a world historical dialog to recover the underpinnings of the Renaissance soul in the Greek exposure to abyssal psychê.

The sixth century author of The Iliad was anything but the naïve, muse-inspired bard he presents as his narrator, nor does his ‘epic’ extol an aristocratic, albeit vexed, Achilles. This original, singular work of art reworks the famous traditional theme of Achilles' wrath, or mênis. The author deploys a revolutionary ad nihilum poesis directed out from the mythos of tradition to the abyss of psyche disclosed through the counter narrative of Achilles’ pothê, the longing that arises from the absence of the fallen leader of a fighting band.

The remarkable failure of generations of readers across the centuries to penetrate to the true meaning and stakes of the work may be attributed not only to the monumentally extended and compounded complexity of its narrative devices, far more complex ultimately than heretofore recognized, but also the trenchant nostalgia, already pilloried four centuries ago by Shakespeare, for naïve mythical origins exploited and critiqued by the author in his own representation of himself as if the mere mortal exponent of the Muse. And this nostalgia for the naïve poet, albeit retranslated from Schiller’s original idealist conception of poetic genius into updated conceptions of still essentially naïve oral poetics, which still holds Homeric Studies in its thrall, continues to propagate methodologies that bear more resemblances to the study of theological traditions than literary or critical studies.

No, not the traditional oral epic. The Iliad, written rather by a single, self-aware, and ironic author in mid-sixth century Athens, unfolds an allegorical critique of the martial aristocracy through Achilles’ relationship with Patroclus. With the onset of his wrath and withdrawal from the fight, Achilles casts his curse of pothê: “someday a longing for Achilles will come upon the sons of Achaeans.” Achilles allows Patroclus, ever at the ready as potential substitute to mitigate the pothê to which his fighting band would be exposed should he fall, rather to substitute for him illegitimately while he still lives. Achilles’ wrath, putative theme of the epic, will, however, only be rescinded once this curse of pothê will have redounded, instead, upon himself with the immitigable pothê he will suffer upon the death of his dearest companion, Patroclus. This pothê occasions Achilles’ exposure to psychê, Patroclus’ psychê, or rather but an imaginary dream vision of such arising as a novel glimmering of conscience. And thus Achilles is exposed to the advent of what is properly human experience, in an unprecedented experience of thauma, or wonder, not so much existential, as ad-sistential; Achilles exposed out there to stand at the limit of the abyss of earth ad nihilum.

The ultimate philosophical dimensions of the study, which offer a crucial step in the recasting of the first movements of the thought of the West, hold out the potential to resuscitate The Iliad, along with Hesiod, for the broader critical audience and thus present another set of demands that generally lie outside the sphere of Homeric or Classical Studies as currently delimited.