Lighthouses and Lightships: A Descriptive and Historical Account of Their Mode of Construction and Organization

Nonfiction, Religion & Spirituality, New Age, History, Fiction & Literature| Author: | William Henry Davenport Adams | ISBN: | 9781465623409 |

| Publisher: | Library of Alexandria | Publication: | March 8, 2015 |

| Imprint: | Language: | English |

| Author: | William Henry Davenport Adams |

| ISBN: | 9781465623409 |

| Publisher: | Library of Alexandria |

| Publication: | March 8, 2015 |

| Imprint: | |

| Language: | English |

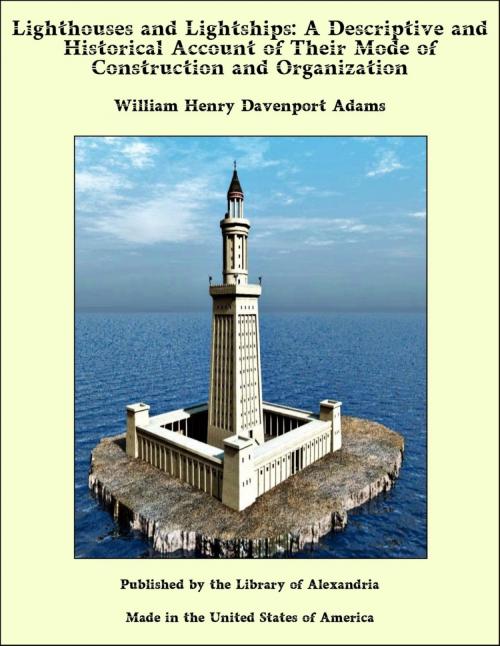

One of the most famous lighthouses of antiquity, as I have already pointed out, was the pharos of Alexandria, which ancient writers included among the Seven Wonders of the World. It might naturally be supposed that the founder of so remarkable a monument of architectural skill would be well known; yet while Strabo and Pliny, Eusebius, Suidas, and Lucian ascribe its erection to Ptolemæus Philadelphus, the wisest and most benevolent of the Ptolemean kings of Egypt, by Tzetzes and Ammianus Marcellinus the honour is given to Cleopatra; and other authorities even attribute it to Alexander the Great. All that can with certainty be affirmed is, that the architect was named Sostrates. Montfaucon, in his great work, endeavours to explain how it is that while we are thus informed as to the architect, we are so doubtful as to the founder, whom, for his part, he believes to have been Ptolemæus. Our ignorance, he says, is owing to the knavery of Sostrates. He wished to immortalize his name; a blameless wish, if at the same time he had not sought to suppress that of the founder, whose glory it was to have suggested the erection. For this purpose Sostrates devised a stratagem which proved successful; deep in the wall of the tower he cut the following inscription: “Sostrates of Cnidos, son of Dexiphanes, to the gods who Protect those who are upon the Sea.” But, mistrustful that King Ptolemæus would scarcely be satisfied with an inscription in which he was wholly ignored, he covered it with a light coat of cement, which he knew would not long endure the action of the atmosphere, and carved thereon the name of Ptolemæus. After a few years the cement and the name of the king disappeared, and revealed the inscription which gave all the glory to Sostrates. Montfaucon, with genial credulity, adopts this anecdote as authentic, and adds: Pliny pretends that Ptolemæus, out of the modesty and greatness of his soul, desired the architect’s name to be engraved upon the tower, and no reference to himself to be made. But this statement is very dubious; it would have passed as incredible in those times, and even to-day would be regarded as an ill-understood act of magnanimity. We have never heard of any prince prohibiting the perpetuation of his name upon magnificent works designed for the public utility, or being content that the architect should usurp the entire honour.

One of the most famous lighthouses of antiquity, as I have already pointed out, was the pharos of Alexandria, which ancient writers included among the Seven Wonders of the World. It might naturally be supposed that the founder of so remarkable a monument of architectural skill would be well known; yet while Strabo and Pliny, Eusebius, Suidas, and Lucian ascribe its erection to Ptolemæus Philadelphus, the wisest and most benevolent of the Ptolemean kings of Egypt, by Tzetzes and Ammianus Marcellinus the honour is given to Cleopatra; and other authorities even attribute it to Alexander the Great. All that can with certainty be affirmed is, that the architect was named Sostrates. Montfaucon, in his great work, endeavours to explain how it is that while we are thus informed as to the architect, we are so doubtful as to the founder, whom, for his part, he believes to have been Ptolemæus. Our ignorance, he says, is owing to the knavery of Sostrates. He wished to immortalize his name; a blameless wish, if at the same time he had not sought to suppress that of the founder, whose glory it was to have suggested the erection. For this purpose Sostrates devised a stratagem which proved successful; deep in the wall of the tower he cut the following inscription: “Sostrates of Cnidos, son of Dexiphanes, to the gods who Protect those who are upon the Sea.” But, mistrustful that King Ptolemæus would scarcely be satisfied with an inscription in which he was wholly ignored, he covered it with a light coat of cement, which he knew would not long endure the action of the atmosphere, and carved thereon the name of Ptolemæus. After a few years the cement and the name of the king disappeared, and revealed the inscription which gave all the glory to Sostrates. Montfaucon, with genial credulity, adopts this anecdote as authentic, and adds: Pliny pretends that Ptolemæus, out of the modesty and greatness of his soul, desired the architect’s name to be engraved upon the tower, and no reference to himself to be made. But this statement is very dubious; it would have passed as incredible in those times, and even to-day would be regarded as an ill-understood act of magnanimity. We have never heard of any prince prohibiting the perpetuation of his name upon magnificent works designed for the public utility, or being content that the architect should usurp the entire honour.