| Author: | Eugène Müntz | ISBN: | 9781783100231 |

| Publisher: | Parkstone International | Publication: | January 17, 2012 |

| Imprint: | Parkstone International | Language: | English |

| Author: | Eugène Müntz |

| ISBN: | 9781783100231 |

| Publisher: | Parkstone International |

| Publication: | January 17, 2012 |

| Imprint: | Parkstone International |

| Language: | English |

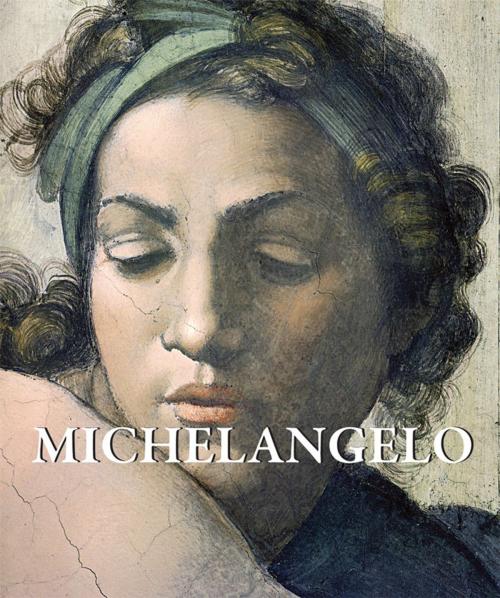

Michelangelo, like Leonardo, was a man of many talents; sculptor, architect, painter and poet, he made the apotheosis of muscular movement, which to him was the physical manifestation of passion. He moulded his draughtsmanship, bent it, twisted it, and stretched it to the extreme limits of possibility. There are not any landscapes in Michelangelo's painting. All the emotions, all the passions, all the thoughts of humanity were personified in his eyes in the naked bodies of men and women. He rarely conceived his human forms in attitudes of immobility or repose. Michelangelo became a painter so that he could express in a more malleable material what his titanesque soul felt, what his sculptor's imagination saw, but what sculpture refused him. Thus this admirable sculptor became the creator, at the Vatican, of the most lyrical and epic decoration ever seen: the Sistine Chapel. The profusion of his invention is spread over this vast area of over 900 square metres. There are 343 principal figures of prodigious variety of expression, many of colossal size, and in addition a great number of subsidiary ones introduced for decorative effect. The creator of this vast scheme was only thirty-four when he began his work. Michelangelo compels us to enlarge our conception of what is beautiful. To the Greeks it was physical perfection; but Michelangelo cared little for physical beauty, except in a few instances, such as his painting of Adam on the Sistine ceiling, and his sculptures of the Pietà. Though a master of anatomy and of the laws of composition, he dared to disregard both if it were necessary to express his concept: to exaggerate the muscles of his figures, and even put them in positions the human body could not naturally assume. In his later painting, The Last Judgment on the end wall of the Sistine, he poured out his soul like a torrent. Michelangelo was the first to make the human form express a variety of emotions. In his hands emotion became an instrument upon which he played, extracting themes and harmonies of infinite variety. His figures carry our imagination far beyond the personal meaning of the names attached to them.

Michelangelo, like Leonardo, was a man of many talents; sculptor, architect, painter and poet, he made the apotheosis of muscular movement, which to him was the physical manifestation of passion. He moulded his draughtsmanship, bent it, twisted it, and stretched it to the extreme limits of possibility. There are not any landscapes in Michelangelo's painting. All the emotions, all the passions, all the thoughts of humanity were personified in his eyes in the naked bodies of men and women. He rarely conceived his human forms in attitudes of immobility or repose. Michelangelo became a painter so that he could express in a more malleable material what his titanesque soul felt, what his sculptor's imagination saw, but what sculpture refused him. Thus this admirable sculptor became the creator, at the Vatican, of the most lyrical and epic decoration ever seen: the Sistine Chapel. The profusion of his invention is spread over this vast area of over 900 square metres. There are 343 principal figures of prodigious variety of expression, many of colossal size, and in addition a great number of subsidiary ones introduced for decorative effect. The creator of this vast scheme was only thirty-four when he began his work. Michelangelo compels us to enlarge our conception of what is beautiful. To the Greeks it was physical perfection; but Michelangelo cared little for physical beauty, except in a few instances, such as his painting of Adam on the Sistine ceiling, and his sculptures of the Pietà. Though a master of anatomy and of the laws of composition, he dared to disregard both if it were necessary to express his concept: to exaggerate the muscles of his figures, and even put them in positions the human body could not naturally assume. In his later painting, The Last Judgment on the end wall of the Sistine, he poured out his soul like a torrent. Michelangelo was the first to make the human form express a variety of emotions. In his hands emotion became an instrument upon which he played, extracting themes and harmonies of infinite variety. His figures carry our imagination far beyond the personal meaning of the names attached to them.