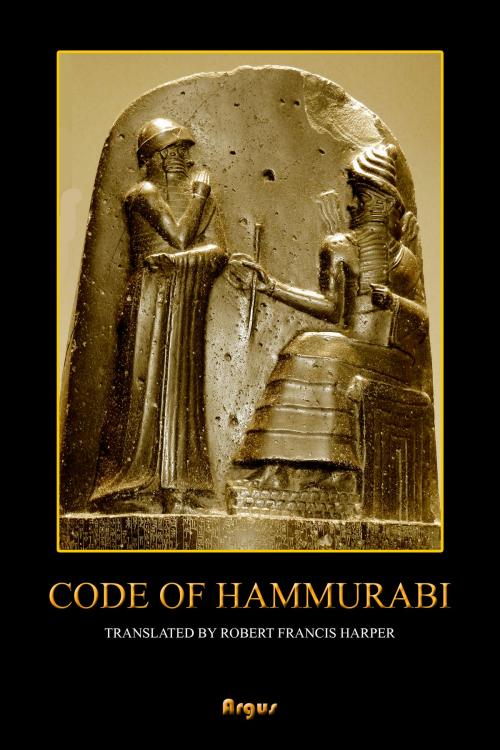

The Code of Hammurabi

Nonfiction, Social & Cultural Studies, Social Science, Crimes & Criminals, Penology, History, Middle East| Author: | Hammurabi, Robert Francis Harper | ISBN: | 1230003084700 |

| Publisher: | Argus | Publication: | February 14, 2019 |

| Imprint: | Language: | English |

| Author: | Hammurabi, Robert Francis Harper |

| ISBN: | 1230003084700 |

| Publisher: | Argus |

| Publication: | February 14, 2019 |

| Imprint: | |

| Language: | English |

The Code of Hammurabi is a well-preserved Babylonian code of law of ancient Mesopotamia, dated back to about 1754 BC (Middle Chronology). It is one of the oldest deciphered writings of significant length in the world. The sixth Babylonian king, Hammurabi, enacted the code. A partial copy exists on a 2.25 metre (7.5 ft) stone stele. It consists of 282 laws, with scaled punishments, adjusting "an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth" (lex talionis) as graded depending on social status, of slave versus free, man or woman.

Babylonia (/ˌbæbɪˈloʊniə/) was an ancient Akkadian-spoken state and cultural area based in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq). A small Amorite-ruled state emerged in 1894 BC, which contained the minor administrative town of Babylon. It was merely a small provincial town during the Akkadian Empire (2335–2154 BC) but greatly expanded during the reign of Hammurabi in the first half of the 18th century BC and became a major capital city. During the reign of Hammurabi and afterwards, Babylonia was called "the country of Akkad" (Māt Akkadī in Akkadian). It was often involved in rivalry with the older state of Assyria to the north and Elam to the east in Ancient Iran. Babylonia briefly became the major power in the region after Hammurabi (fl. c. 1792–1752 BC middle chronology, or c. 1696–1654 BC, short chronology) created a short-lived empire, succeeding the earlier Akkadian Empire, Third Dynasty of Ur, and Old Assyrian Empire. The Babylonian empire, however, rapidly fell apart after the death of Hammurabi and reverted to a small kingdom. Like Assyria, the Babylonian state retained the written Akkadian language (the language of its native populace) for official use, despite its Northwest Semitic-speaking Amorite founders and Kassite successors, who spoke a language isolate, not being native Mesopotamians. It retained the Sumerian language for religious use (as did Assyria), but already by the time Babylon was founded, this was no longer a spoken language, having been wholly subsumed by Akkadian. The earlier Akkadian and Sumerian traditions played a major role in Babylonian and Assyrian culture, and the region would remain an important cultural center, even under its protracted periods of outside rule. The earliest mention of the city of Babylon can be found in a clay tablet from the reign of Sargon of Akkad (2334–2279 BC), dating back to the 23rd century BC. Babylon was merely a religious and cultural centre at this point and neither an independent state nor a large city; like the rest of Mesopotamia, it was subject to the Akkadian Empire which united all the Akkadian and Sumerian speakers under one rule. After the collapse of the Akkadian empire, the south Mesopotamian region was dominated by the Gutian people for a few decades before the rise of the Third Dynasty of Ur, which restored order to the region and which, apart from northern Assyria, encompassed the whole of Mesopotamia, including the town of Babylon.

"Only one eye for one eye", also known as "An eye for an eye" or "A tooth for a tooth", or the law of retaliation, is the principle that a person who has injured another person is to be penalized to a similar degree, and the person inflicting such punishment should be the injured party. In softer interpretations, it means the victim receives the [estimated] value of the injury in compensation. The intent behind the principle was to restrict compensation to the value of the loss. The principle is sometimes referred using the Latin term lex talionis or the law of talion. The English word talion (from the Latin talio) means a retaliation authorized by law, in which the punishment corresponds in kind and degree to the injury.

The Code of Hammurabi is a well-preserved Babylonian code of law of ancient Mesopotamia, dated back to about 1754 BC (Middle Chronology). It is one of the oldest deciphered writings of significant length in the world. The sixth Babylonian king, Hammurabi, enacted the code. A partial copy exists on a 2.25 metre (7.5 ft) stone stele. It consists of 282 laws, with scaled punishments, adjusting "an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth" (lex talionis) as graded depending on social status, of slave versus free, man or woman.

Babylonia (/ˌbæbɪˈloʊniə/) was an ancient Akkadian-spoken state and cultural area based in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq). A small Amorite-ruled state emerged in 1894 BC, which contained the minor administrative town of Babylon. It was merely a small provincial town during the Akkadian Empire (2335–2154 BC) but greatly expanded during the reign of Hammurabi in the first half of the 18th century BC and became a major capital city. During the reign of Hammurabi and afterwards, Babylonia was called "the country of Akkad" (Māt Akkadī in Akkadian). It was often involved in rivalry with the older state of Assyria to the north and Elam to the east in Ancient Iran. Babylonia briefly became the major power in the region after Hammurabi (fl. c. 1792–1752 BC middle chronology, or c. 1696–1654 BC, short chronology) created a short-lived empire, succeeding the earlier Akkadian Empire, Third Dynasty of Ur, and Old Assyrian Empire. The Babylonian empire, however, rapidly fell apart after the death of Hammurabi and reverted to a small kingdom. Like Assyria, the Babylonian state retained the written Akkadian language (the language of its native populace) for official use, despite its Northwest Semitic-speaking Amorite founders and Kassite successors, who spoke a language isolate, not being native Mesopotamians. It retained the Sumerian language for religious use (as did Assyria), but already by the time Babylon was founded, this was no longer a spoken language, having been wholly subsumed by Akkadian. The earlier Akkadian and Sumerian traditions played a major role in Babylonian and Assyrian culture, and the region would remain an important cultural center, even under its protracted periods of outside rule. The earliest mention of the city of Babylon can be found in a clay tablet from the reign of Sargon of Akkad (2334–2279 BC), dating back to the 23rd century BC. Babylon was merely a religious and cultural centre at this point and neither an independent state nor a large city; like the rest of Mesopotamia, it was subject to the Akkadian Empire which united all the Akkadian and Sumerian speakers under one rule. After the collapse of the Akkadian empire, the south Mesopotamian region was dominated by the Gutian people for a few decades before the rise of the Third Dynasty of Ur, which restored order to the region and which, apart from northern Assyria, encompassed the whole of Mesopotamia, including the town of Babylon.

"Only one eye for one eye", also known as "An eye for an eye" or "A tooth for a tooth", or the law of retaliation, is the principle that a person who has injured another person is to be penalized to a similar degree, and the person inflicting such punishment should be the injured party. In softer interpretations, it means the victim receives the [estimated] value of the injury in compensation. The intent behind the principle was to restrict compensation to the value of the loss. The principle is sometimes referred using the Latin term lex talionis or the law of talion. The English word talion (from the Latin talio) means a retaliation authorized by law, in which the punishment corresponds in kind and degree to the injury.