The Seventh Letter

Nonfiction, Religion & Spirituality, Philosophy, Ancient, Fiction & Literature, Poetry, Literary Theory & Criticism| Author: | Plato | ISBN: | 9780599461789 |

| Publisher: | Lighthouse Books for Translation Publishing | Publication: | May 14, 2019 |

| Imprint: | Lighthouse Books for Translation and Publishing | Language: | English |

| Author: | Plato |

| ISBN: | 9780599461789 |

| Publisher: | Lighthouse Books for Translation Publishing |

| Publication: | May 14, 2019 |

| Imprint: | Lighthouse Books for Translation and Publishing |

| Language: | English |

The Seventh Letter of Plato is an epistle that tradition has ascribed to Plato. It is by far the longest of the epistles of Plato and gives an autobiographical account of his activities in Sicily as part of the intrigues between Dion and Dionysius of Syracuse for the tyranny of Syracuse.

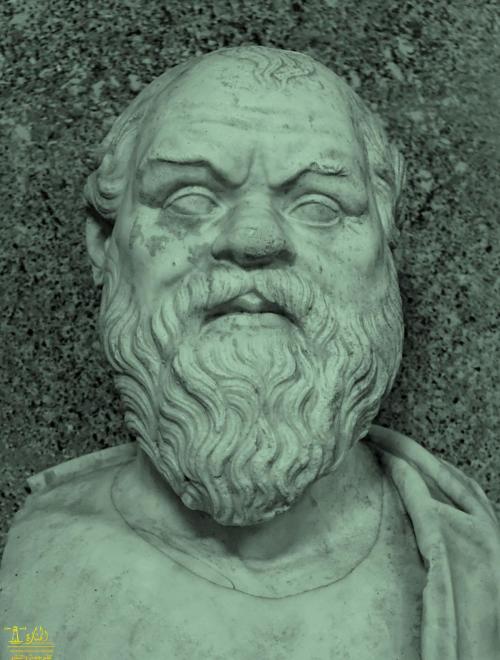

Plato, (born 428/427 bce, Athens, Greece—died 348/347, Athens), ancient Greek philosopher, student of Socrates (c. 470–399 bce), teacher of Aristotle (384–322 bce), and founder of the Academy, best known as the author of philosophical works of unparalleled influence.

Building on the demonstration by Socrates that those regarded as experts in ethical matters did not have the understanding necessary for a good human life, Plato introduced the idea that their mistakes were due to their not engaging properly with a class of entities he called forms, chief examples of which were Justice, Beauty, and Equality. Whereas other thinkers—and Plato himself in certain passages—used the term without any precise technical force, Plato in the course of his career came to devote specialized attention to these entities. As he conceived them, they were accessible not to the senses but to the mind alone, and they were the most important constituents of reality, underlying the existence of the sensible world and giving it what intelligibility it has. In metaphysics Plato envisioned a systematic, rational treatment of the forms and their interrelations, starting with the most fundamental among them (the Good, or the One); in ethics and moral psychology he developed the view that the good life requires not just a certain kind of knowledge (as Socrates had suggested) but also habituation to healthy emotional responses and therefore harmony between the three parts of the soul (according to Plato, reason, spirit, and appetite). His works also contain discussions in aesthetics, political philosophy, theology, cosmology, epistemology, and the philosophy of language. His school fostered research not just in philosophy narrowly conceived but in a wide range of endeavours that today would be called mathematical or scientific.

The son of Ariston (his father) and Perictione (his mother), Plato was born in the year after the death of the great Athenian statesman Pericles. His brothers Glaucon and Adeimantus are portrayed as interlocutors in Plato’s masterpiece the Republic, and his half brother Antiphon figures in the Parmenides. Plato’s family was aristocratic and distinguished: his father’s side claimed descent from the god Poseidon, and his mother’s side was related to the lawgiver Solon (c. 630–560 bce). Less creditably, his mother’s close relatives Critias and Charmides were among the Thirty Tyrants who seized power in Athens and ruled briefly until the restoration of democracy in 403.

Plato as a young man was a member of the circle around Socrates. Since the latter wrote nothing, what is known of his characteristic activity of engaging his fellow citizens (and the occasional itinerant celebrity) in conversation derives wholly from the writings of others, most notably Plato himself. The works of Plato commonly referred to as “Socratic” represent the sort of thing the historical Socrates was doing. He would challenge men who supposedly had expertise about some facet of human excellence to give accounts of these matters—variously of courage, piety, and so on, or at times of the whole of “virtue”—and they typically failed to maintain their position.

The Seventh Letter of Plato is an epistle that tradition has ascribed to Plato. It is by far the longest of the epistles of Plato and gives an autobiographical account of his activities in Sicily as part of the intrigues between Dion and Dionysius of Syracuse for the tyranny of Syracuse.

Plato, (born 428/427 bce, Athens, Greece—died 348/347, Athens), ancient Greek philosopher, student of Socrates (c. 470–399 bce), teacher of Aristotle (384–322 bce), and founder of the Academy, best known as the author of philosophical works of unparalleled influence.

Building on the demonstration by Socrates that those regarded as experts in ethical matters did not have the understanding necessary for a good human life, Plato introduced the idea that their mistakes were due to their not engaging properly with a class of entities he called forms, chief examples of which were Justice, Beauty, and Equality. Whereas other thinkers—and Plato himself in certain passages—used the term without any precise technical force, Plato in the course of his career came to devote specialized attention to these entities. As he conceived them, they were accessible not to the senses but to the mind alone, and they were the most important constituents of reality, underlying the existence of the sensible world and giving it what intelligibility it has. In metaphysics Plato envisioned a systematic, rational treatment of the forms and their interrelations, starting with the most fundamental among them (the Good, or the One); in ethics and moral psychology he developed the view that the good life requires not just a certain kind of knowledge (as Socrates had suggested) but also habituation to healthy emotional responses and therefore harmony between the three parts of the soul (according to Plato, reason, spirit, and appetite). His works also contain discussions in aesthetics, political philosophy, theology, cosmology, epistemology, and the philosophy of language. His school fostered research not just in philosophy narrowly conceived but in a wide range of endeavours that today would be called mathematical or scientific.

The son of Ariston (his father) and Perictione (his mother), Plato was born in the year after the death of the great Athenian statesman Pericles. His brothers Glaucon and Adeimantus are portrayed as interlocutors in Plato’s masterpiece the Republic, and his half brother Antiphon figures in the Parmenides. Plato’s family was aristocratic and distinguished: his father’s side claimed descent from the god Poseidon, and his mother’s side was related to the lawgiver Solon (c. 630–560 bce). Less creditably, his mother’s close relatives Critias and Charmides were among the Thirty Tyrants who seized power in Athens and ruled briefly until the restoration of democracy in 403.

Plato as a young man was a member of the circle around Socrates. Since the latter wrote nothing, what is known of his characteristic activity of engaging his fellow citizens (and the occasional itinerant celebrity) in conversation derives wholly from the writings of others, most notably Plato himself. The works of Plato commonly referred to as “Socratic” represent the sort of thing the historical Socrates was doing. He would challenge men who supposedly had expertise about some facet of human excellence to give accounts of these matters—variously of courage, piety, and so on, or at times of the whole of “virtue”—and they typically failed to maintain their position.